Anyone who claims that the fate of the climate talks is bound to the fate of the Occupy movement better expect a bit of skepticism in return. Now, if it were Occupy and the Climate Justice movement, that would be a different story! Both are complex social movements, and both are driving hard for economic justice. Their overlap is inevitable. But the negotiations themselves? What have they to do with economic justice? What have they to do with the great divide between “the 1%” and “the 99%”?

It’s an easy question to ask. Too easy, actually. It’s a question that raises others…

Beyond vague talk about “the most vulnerable countries and people,” few of us are really prepared to approach the climate crisis as a justice problem. So it should be said that it didn’t have to be this way. If justice had long been a major part of environmental politics, we’d be in better shape today. But it hasn’t been, not until recently, and the truth is that Big Green still isn’t really on board with justice environmentalism. In fact, it’s fair to say that today’s progressive enviros are the inheritors of a long tradition, and that it’s not a uniformly admirable one. The climate politics mainline, in particular, has long focused, almost exclusively, on the technical side of the transition problem. Not that there’s any hope without a technology revolution, but must it come packaged with a refusal to understand, let alone confront, the economic divide that’s at the core of the global climate-policy deadlock?

Things are changing now, or at least they could. But the past matters.

Remember Copenhagen? Remember the vitriol of the blame game that followed Copenhagen? Do try, because soon we’re going to see what, if anything, we’ve learned in the two years since that great debacle. As I write this, Durban, South Africa (the next Conference of Parties to the Climate Convention) is coming right up, and it will almost certainly join Copenhagen on the long list of grim, poorly-reported failures to make the international breakthrough that we so badly need. As Durban approaches, and then passes, we’re all going to have to decide what the hell we think is actually going on.

Important things will happen in Durban, but they’ll not alone set the tone of the next year. That role will be reserved for the economy, and the US election, and – for the aficionados among us – the early drafts of the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment report. In the meantime, beware China bashing, which was the preferred mode of rationalization after Copenhagen, at least in the North (see Mark Lynas’ genre milestone here). It could easily return again. To see the danger, glance at Joe Romm’s recent report of China’s booming emissions. This boom, and how it’s understood, will weigh more on the overall prospect than the minutia of the negotiations. Not that I’m specifically criticizing Romm, but the fact is that, as a community, we’re poorly prepared to understand China’s trajectory, or its implications. So he can says that “Chinese CO2 Emissions Now Exceed U.S.’s By 50%,” and the numbers seem to speak for themselves.

They don’t actually, but they seem to.

And, most likely, what they seem to say is that the climate negotiations no longer matter. That the Chinese economy is beyond all control. And, with the other “big emitters” (e.g. India) straining to follow along on the same path as the Chinese, that we’re basically toast. That the only real hope of containing the emissions of the “emerging economies” is energy-system revolution – technology, again, as the savior. That “soft” concerns like “equity” – it would be better to be precise and say something like “economic justice in a climate constrained world,” but never mind that for now – have little if anything to contribute.

The “climate realists” (as they fancy themselves) encourage such views, for realism-as-we-know-it sees only power, national interest, and merciless competition dynamics that leave little room for negotiated political restraint. See for example, Dave Robert’s love-letter to David Victor’s realism, here. The truth, however, is rather more complex, and it includes the fact that the negotiations matter a great deal. They matter for the beginnings they’ve made, the progress they incrementally mark out, and, frankly, because they exist. If and when we ever get serious, they give us a place to build.

But we’re not going to get serious until we’re willing to talk about economic division.

Which brings us back to Occupy. Which has, in a few short months, managed to refocus the political battle on economic inequality, and to illuminate this inequality as the (not so) secret substructure of modern life. As a substructure that, remarkably, we’d almost given up on noticing. By so doing, it has raised the possibility of a similar refocusing within the climate world, one that would be particularly welcome, and particularly challenging. Because when it comes to climate, inequality necessarily involves both the domestic and international, both the rich/poor and the North/South divides. When it comes to climate, neither side of our twice-divided world can be ignored, or reduced to the other.

Complicated? Yes, but one of the amazing things about Occupy is the way it has dissolved the image of complexity as an obstacle to clear thinking and sharp conclusion. The way it has stripped away the camouflage, and made the simplicity of economic division visible. We could use a similar magic within the climate war, where complexity is always the final excuse for paralysis.

History is racing ahead. Finance capital is out of control, and this is a challenge to us all. The denialist movement has come out as a division of the right-wing machine, and thus sealed its own doom. The renewables industry is growing by 30% a year, and thus offering us a rare straw that we had better grasp. The international economy is changing fast, and we can’t pretend to know exactly how. America is in crisis. In all this it’s easy to lose perspective, and to forget the inconvenient reality that, even in world of crisis, the environmental crisis must take pride of place, and that the climate crisis is it’s cutting edge, and that our efforts to “mitigate” this crisis have thus far come up very short indeed. That compared to the action that’s needed, we’re going nowhere.

Nor will we go anywhere without a breakthrough in the negotiations. The climate crisis, after all, is a commons problem. The commons problem from hell. Absent a well-functioning global regime, we can’t honestly hope for the global surge of transformative innovation and renewal that’s necessary to hold the risks within manageable levels. And we’ll not get a well-functioning regime unless it’s fair, and seen to be fair.

You may not like it, but there it is.

***

A friend of mine, an officer of a major climate foundation, recently sent out an email entitled “EU begging for help in China.” He pointed to an article in the Financial Times (it’s behind a paywall, but see this similar piece in the New York Times), and argued that the financial crisis is redefining North-South relations. And he opined that “this will have repercussions on the climate debate, for sure.”

He’s definitely right about this. And he might have added that the repercussions will be coming soon. Because when Durban rolls around, it’s going to be dominated by an exhausted but inevitable battle to save the Kyoto Protocol, which the US, backed by Canada, Russia, and Japan, seems intent on pushing off the rails. Which the Chinese, in turn, will play for all the international good will that they can muster. And which the journalists will spin and interpret for all they’re worth. Which might not be all that much. Because whatever happens in the negotiations, they’ll be seen against the background of the financial crisis, and thus we’re sure to be treated to a huge helping of snarky coverage of emerging-market mercantilists (think China) who refuse to pull their own weight.

If this was a story of figures and facts, I’d take this opportunity to explain yet again that China is doing much more than the US to abate its carbon emissions, and I’d cite chapter and verse. But China is not my topic, so let me simply point to this recent analysis of rich world and developing world emission-reduction pledges, which was written by SEI scientist Sivan Kartha (full disclosure: Sivan is a climate-equity geek and a colleague of mine). And, for brave souls who actually want to understand the big picture, let me add this link to Development without Carbon: Climate and the Global Economy through the 21st Century, a fabulous analysis that was just published by E3 Network economist Liz Stanton.

In any case, the immediate topic here is inequality and politics and, inevitably, ideology.

To see how difficult it can be to tell the difference between politics and ideology, click over to Foreign Affairs, which recently published Arvind Subramanian’s The Inevitable Superpower: Why China’s Dominance Is a Sure Thing. Here’s one of Subramanian’s blurbs:

“What if, contrary to common belief, China’s economic dominance is a present-day reality rather than a faraway possibility? What if the renminbi’s takeover of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency is not decades, but mere years, away? And what if the United States’ economic pre-eminence is not, as many economists and policymakers would like to believe, in its own hands, but China’s to determine?”

Well, what if? What would this mean for the climate negotiations? Would it, in particular, mean that the US has recently been right to insist – as it continues to do – that the whole idea of a world divided between wealthy developed and poor developing countries is obsolete?

Probably not. But it would sure mean something. It would mean, to exaggerate just a bit, that the world is “turning upside down” (as some of my wonkiest friends have taken to saying) and that any notion of rich-world “responsibility” – as in “common but differentiated responsibilities” – is altogether obsolete.

So, is the world really turning upside down?

I don’t think so.

***

I don’t deny the power of China’s emergence. But even if it does soon “eclipse” the US, in state-to-state power-political terms, this won’t be the whole story. Because – to get back to Occupy – the North is still the heartland of the rich. And even China’s great boom – which, by the way, has lifted an immense number of people out of poverty – has not changed this very much at all.

Cut to the Global Wealth Report that’s just been released by the gnomes at Credit Suisse. Start with Millionaires Control 39% of Global Wealth, a nice post by our friends at the Wall Street Journal that announced the report’s existence and a few of its conclusions. (To be precise, the report says that the world’s millionaires make up 0.5% of the world’s adult population and control 38.5% of the world’s wealth). It got my attention because these are global numbers, and because Credit Suisse’s researchers deal not in income, the usual recourse of development economists, but actual wealth. Capital and real estate and gold and such.

The report contains international wealth-per-adult numbers. Compare the US and Chinese numbers, for both 2000 and 2011, and you get this amazing takeaway – China’s wealth per adult has increased much more (from $6,000 to $21,000 a year) in percentage terms, but the US’s has increased much more (from $192,000 to $248,000) in absolute terms.

Think about that for a second. The recent increase in Chinese personal wealth has been amazing, but what’s even more interesting, from the point of view of the fair global cost-sharing problem that’s at the core of the climate impasse, is that wealth is increasing even faster in the US than it is in China. And that this is happening even as we are repeatedly told that the Chinese are eating our lunch.

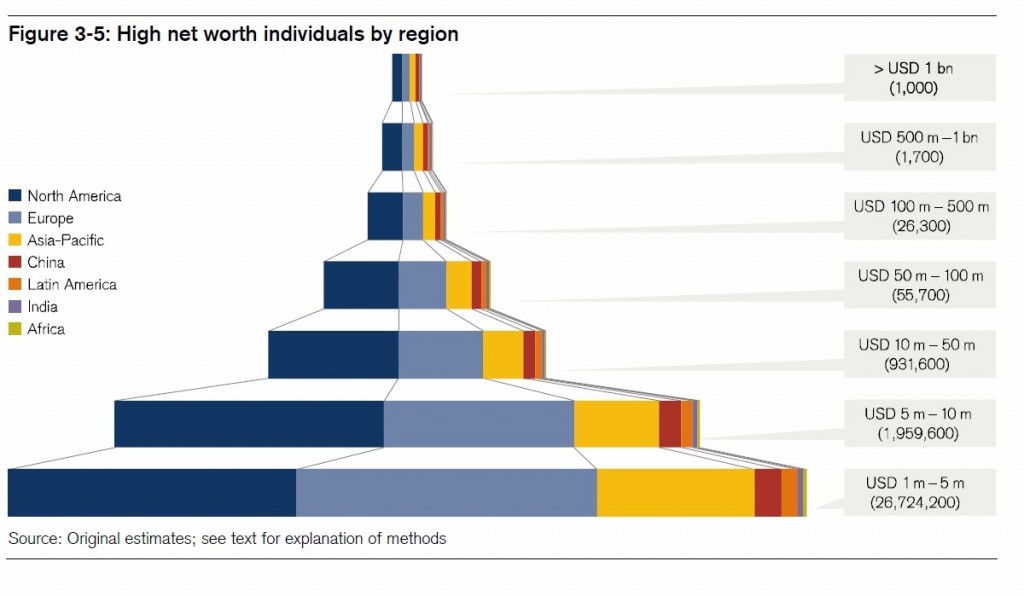

Take a look at Figure 6:

Here’s a bit of discussion from the report, but first you need a few acronyms: HNW means “high net worth” and UHNW means “ultra high net worth.” USD means “United States Dollar.”

“Our figures for mid-2011 indicate that there were 29.6 million HNW with wealth from USD 1 million to USD 50 million, of whom the vast majority (26.7 million) fall in the USD 1-5 million range. North America used to host the greatest number of members, and still accounts for 11 million HNW individuals (37% of the total), but membership in the North American regions has been surpassed this year by residents of Europe (37.2% of the total). Asia-Pacific countries excluding China and India are home to 5.7 million members (19.2%), and we estimate that there are now just over 1 million HNW individuals in China (3.4% of the global total). The remaining 937,000 HNW individuals (3.2% of the total) reside in India, Africa or Latin America.

Ultra high net worth

Our figures indicate a global total of 84,700 UHNW individuals with net assets exceeding USD 50 million. Of these, nearly 29,000 are world at least USD 100 million and 2,700 have assets above USD 500 million. North America dominate the regional ranking, with 37,500 UHNW residents (44%), while Europe hosts 23,700 individuals (28%) and 13,000 (15% reside in Asia-Pacific countries, excluding China and India.

In terms of single countries, the USA leads by a huge margin with 34,400 UHNW individuals, equivalent to 42% of the group. The recent fortunes created in China have propelled China into second place with 5,400 representatives.”

What’s the takeaway? Well, the report gives figures for the “Top 1%,” on a per-country basis. It turns out that 27.85% of them live in the US, and 3.54% of them live in China. Is that a lot of rich people in China? Well, yes, but not compared to the number in the US. And don’t forget that rich people in the US are richer than rich people in China, and getting richer still.

So how should we understand the claim that China is “eclipsing” the US? And what does this eclipse, if in fact it’s taking place, imply for the climate negotiations – in Durban, sure, but mostly beyond Durban, when the next major phase of the negotiation, the global phase, is going to eventually have to take place?

And given that so many of the rich – who ultimately should pay much of the cost of the climate transition, and indeed much of the cost of the future – still abide in the North, what does it say about fair, and unfair, divisions of the international burden? And about which nations should take on which obligations? And, critically, what does it mean that so much of the world’s wealth is ensconced in America, a land of wide and deepening poverty?

***

The last 30 years have seen a hollowing out of the US economy. We all know that this “deindustrialization” has had immense negative impacts on the American people, but we rarely consider that it may also have catastrophic global consequences.

The wealth stats indicate that America is still number one, at least as a place for the rich to hide out in. But how does the surfeit of rich Americans bear on the impasse in the climate negotiations? The standard explanation has them mattering very little. Subramanian, for example, focuses not on individual wealth, but instead on national GDP, national trade, and the extent to which a nation is “a net creditor to the rest of the world.” These, he argues, are the decisive factors when it comes to the constitution of national power, which from any broadly realist perspective is what international negotiations are all about. A simple way to say this is that, from the point of view of states, it’s trade and sovereign wealth that matter, and that they overbear the wealth and capacity of citizens (or residents).

But is this the whole story? I don’t think so. I think, rather, that inequality within countries is key to the politics of climate mobilization among countries. This is true for lots of reasons, one of the most important being that countries that do not protect their own citizens lose their political legitimacy, and thus their ability to act. Timmons Roberts, an activist academic and a close observer of the negotiations, even argues in Global Environmental Change that “the roots of the worst stubbornness by the US in recent climate talks lie in growing insecurity about its ability to provide jobs for its workers in a future where all sorts of work is moving to China and India.”

If this is true (and why wouldn’t it be?) it invites an extremely sharp interpretation. To wit, that the corporations, and the ideologues, and all the others that chose to deindustrialize America also chose (though they wouldn’t put it this way) to create a new United States that would be so “insecure” in the face of the climate threat that it refuses to lead, or to act, or even to allow others to act, save in the most timid and inadequate ways. By so doing they may have so poisoned the system of international governance that we will simply be unable to mobilize an effective response to the global climate threat.

Which really is an existential one.

The point here is that inequality and its related dysfunctions are critical obstacles to a successful climate transition. They are obstacles within countries, where the 1% are so coddled by their riches that they will not even notice the rising terrors of the warming world, while many of the 99% are so insecure, and so anxious, that they fear, or can be made to fear, even the policy reforms that they need to protect themselves and their families. And inequality is an international obstacle as well, for it greatly interferes with the goal of negotiating a regime that is both practical and fair. The UN’s notion of “common but differentiated responsibility and respective capability” tells the tale clearly enough, for as a principle of international law it was obviously intended to apply to nations. But what happens when some nations – like the US – are effectively captured, and crippled, by elites that disdain even the notion of international responsibility?

The problem here is “governance failure.” Or maybe we should just call it “decadence.” The United States may at this point be so weakened by rot and ideology that it is unable even to act in its own interests, let alone the interests of its people, let alone the interests of humanity as a whole. Sort of like Russia. Or Saudi Arabia. If this is the case, and to some extent it clearly is, then the challenge of national renewal, of “taking back America” is even greater, and more pressing, than we had previously believed.

– Tom Athanasiou