The bad news is that the climate/energy push just crashed and burned in the Senate. The good news is that, in the wake of that crash, the US climate community is having a robust Big Think. The last time we had such an exchange was back after what, for lack of a better term, I will call the Great Copenhagen Disappointment. Which raises an interesting question – do we only debate, openly and seriously, after we lose?

If so, and judging by the situation in Bonn, where an inconclusive post-Copenhagen “intersessional” just shambled a bit closer to December’s rematch in Cancun, we’re up for another round of disputation soon. Not, of course, that disappointment in Cancun is certain. It’s still possible that the wealthy countries are going to actually come up with the “fast start finance” that they promised back in Copenhagen. Maybe they’ll even go beyond fast-start finance, and actually start acting like they want to make a meaningful international deal. Because, frankly, it’s their move.

But while we’re waiting, it’s best to admit that the level of despair is high and rising. In America, matters could still get worse. And as for the international negotiations, well let’s just say that a certain pall has descended. The US has been accused of being bloody minded, and not without cause. Everywhere, expectations are being lowered. Consider the Copenhagen Accord. After Denmark, it was widely – and justly – disparaged. But now, with the negotiations fraying, who can but notice that, by moving the world’s nations to commit pledges to paper, it at least allows us to see – with distressing clarity – just exactly where we are.

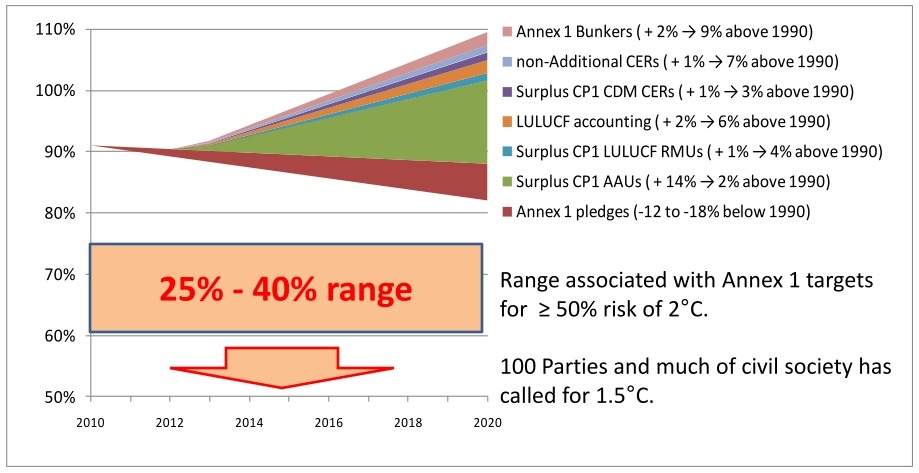

The bottom line: the Copenhagen Accord sets up a “transparent” situation in which research teams around the world can sum and evaluate both the total size of the global emissions reduction pledge, and the total size of the Annex 1 (rich world) pledge. Alas, both are terribly low. They are low with respect to the demands of the 1.5C and 2C temperature targets that, between them, define the emergency mobilization pathways that are our best hope. And they are even low with respect to the problematic, though oft-supported (even, it is said, by the IPCC) claim that, to hold the 2C line, the Annex 1 countries must reduce emissions, by 2020, by at least 25%, and preferably 40%, below their 1990 levels.

The problem is that (excluding the US) Annex 1’s “aggregate pledges” add up to cuts of only 17-25% below 1990 levels by 2020. And when you factor the US’s pledge (which is still on the table) to reduce emissions by 17% below the 2005 level by 2020 — a pledge that is almost as paltry as it is unacceptable to the American right — you dilute the total rich-world 2020 pledge down to 12-18% below 1990.

This is not a serious target, and it directly implies a global regime of extremely inadequate ambition. But what if we, as they say, get realistic What if we take account of the timidity of an Administration that, after all, faces an explicitly nihilistic Republican opposition Wouldn’t it at least be a break with the past, and maybe, just maybe, enough to get the ball rolling

The problem is that the ball only rolls if the pledges perform as advertised. And this, as it turns out, is not the plan. Because the Annex 1 Copenhagen pledges, though widely trumpeted by governments around the world, are rife with extremely significant loopholes.

The mere existence of such loopholes is not news – determinedly bogus land-use emissions accounting, non-additional international offsets, “hot air” from the former Soviet states, unaccounted “bunker” emissions associated with international travel and shipping – the climate NGOs have been talking about them for years, to anyone who would listen. What is news is that, now that the science is clear (see for example Mitigating climate change through reductions in greenhouse gas emissions: is it possible to limit global warming to no more than 1.5°C?) and the pledges have been collected by the UN Secretariat, the total size of the Annex 1 loophole can be properly, quantitatively, evaluated. And, according to a series of recent accountings – among them a presentation, by Sivan Kartha of the Stockholm Environment Institute, at a UNFCCC workshop in Bonn (described in this excellent summary by the Third World Network), and a report, The Integrity Gap: Copenhagen Pledges and Loopholes, published by Simon Terry at the Sustainability Council of New Zealand – it’s huge.

In fact, even when conservative assumptions are used, the Copenhagen pledges contains so many loopholes that, taken together, they sum to 21% of 1990 emissions, a number that entirely negates the pledges themselves! So that the official, well-publicized global 2020 emissions reductions target of 12-18% actually means that emissions levels large enough to reach 3-9% above 1990 would be allowed. Which is (a technical point but one that climate wonks will appreciate) actually more than the business-as-usual projection!

Here’s a picture, from Kartha’s presentation in Bonn:

All told, it’s a grim situation. But at the same time, it’s an interesting one, because the cat is out of the bag. The rich world’s negotiating position is manifestly bankrupt, and it will remain so until, at a minimum, these loopholes are closed. Moreover, this is obvious, just as it is obvious that Obama-era climate policy — expensive though it’s been in the currency of international trust — has nevertheless failed to break the Senate deadlock. And that, by its stasis, the US goes a long way towards paralyzing the rest of the world. And that this paralysis is extremely convenient, to recalcitrant elites everywhere.

Still, the situation is quite unstable. Look again at the top of Kartha’s graph, which describes a rising puce line that, frankly, we’re just not going to ride. Not the way the science is going, not the way the impacts are manifesting, not without a legitimation crisis of major and unpredictable proportions! And if we don’t, the only other alternative we’ll have is to do something new. Exactly what in it will be isn’t clear at the moment, but I at least have found one bit of odd consolation in the situation. I’ve finally been able to quiet the doubting voices in my head, the ones that say that telling the truth about the scale of US international obligations is just too dangerous, that doing so is throwing red meat to the right wing, and endangering the Congressional breakthrough that is our best hope. These voices, frankly, have been troubling me, but after the last year, I no longer fear that bluntness can make the opposition any more implacable and hell-bent than it already is.

Dave Robert seems to me to support this conclusion, in a widely-circulated piece in Grist, wherein he strongly claimed that the real obstacles to US action are the structure of the Senate (a relic of slavery!), the degenerate state of the American right, and, of course, the economic crisis, and that the many policy disputes that roil the climate movement, sharp and significant though they may be, are entirely secondary. And Bill McKibben clearly does as well, when he argues that, as a matter of strategy, we must tell the truth – “we have to ask for what we actually need, not what we calculate we might possibly be able to get.” In the course of his argument, by the way, McKibben unearths a lovely quote from David Brower, to the effect that:

“We are to hold fast to what we believe is right, fight for it, and find allies and adduce all possible arguments for our cause. If we cannot find enough vigor in us or them to win, then let someone else propose the compromise. We thereupon work hard to coax it our way. We become a nucleus around which the strongest force can build and function.”

Taken together, I read Roberts, and McKibben, and Brower, and my own sense of the terrain to imply that we have both an opportunity and a responsibility to speak freely.

Even I, with my insistent belief that a large measure of global economic justice is necessary to any viable global climate regime, even I am free to speak my mind, without worrying that I’ll squirrel the deal for my realist friends in Washington. True, I have to be careful about how I talk about costs (as in the aggregate global cost of saving our civilization, which, frankly, is going to be a bit high), but all in all I can relax. Today’s Republicans already believe, or claim to believe, that environmentalism = socialism = the UN = dictatorship, and that Sweden is Hell on Earth. Given this, how much harm can it possible do to add one more small wrinkle to the mix – like a frank discussion of the impasse in the global negotiations?

— Tom Athanasiou